Livestock is a beautiful thing. It is literally the staff of life for tens of millions of people especially in marginal areas. It has accompanied humans for some 10,000 years and is an indelible part of countless cultures.

But that should not lead us to a blanket endorsement of all livestock. We need to acknowledge that if livestock is managed in confinement, solely oriented at maximising yields, it causes massive damage to the environment, eliminating biodiversity, polluting air, water and soils, posing public health threats and involving cruelty to animals.

So livestock as such is neither good nor bad – it is all a question of management.

It is vexing to observe at the on-going Climate COP in Baku how livestock concerned people divide into either pro or contra.

Contra are the the parties that are betting on plant based products, exemplified by the TAPP Coalition of vegan companies, ostensibly dedicated to ‘fair pricing’ of meat and dairy.

In favour are the usual suspects for whom livestock can do no harm, and it is all about working towards net-zero. A chief protagonist here is the IICA – the Inter-American Institute for Cooperation on Agriculture- which represents the interests of the meat and dairy industries.

Thus we have two interest groups pitched against each other: animal versus plant based industries, while independent science seems to be sadly absent. The CGIAR has a Food and Agriculture pavilion, but the programme is all about finance, undoubtedly to mobilize funding for less emissions from livestock, rather than fundamentals.

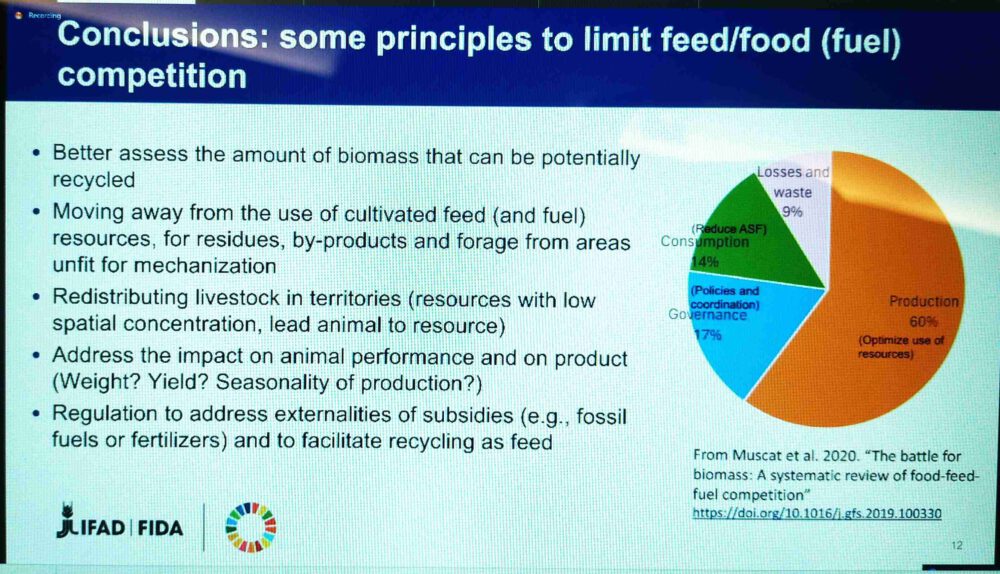

I hope it is uncontroversial to say that one of the fundamental requirements for sustainable food production is for it to mimic nature as much as possible. And, as we all know, nature is composed of both plants and animals. Therefore, we should not thrive for food systems that are either/or. Instead, we need a balance between the two, to achieve recycling of nutrients, without depending on fossil fuels. I can’t speak for the crop people, but animal science generally looks at livestock in isolation, pre-occupied with raisng performance, without considering its relationship to plants. And its mainstream seems to have been captured by industrial interests. Only that can explain the almost totemistic fixation on livestock’s Green House Gas emissions, speak methane, that has taken over research and funding.

Yes, ruminants emit methane which warms/heats the atmosphere – but this is part of a natural cycle. This kind of biogenic methane is recycled CO2 that is circulating in the atmosphere anyway. It is a different thing than the CO2 added to the atmosphere by extracting fossil fuels and which we desperately need to control. Yet, while the livestock crowd is on fire about reducing methane, it is strangely silent about the fossil fuel that is required for sustaining industrial livestock production with its massive energy requirements for planting, fertilizing, protecting from pests, harvesting and transporting feed. Sure, there are lifecycle analyses and, there is GLEAM, the Global Livestock Environmental Assessment Model, but these are so complicated I wonder if anybody ever uses them for guidance when designing livestock systems.

This pre-occupation with methane directly plays into the hands of industrial interests, because it ignores their massive use of fossil fuels and justifies all kinds of new technologies to decrease methane. Apart from that, reducing livestock’s environmental impact to methane emissions, conveniently ignores all the other negative impacts of livestock industries on biodiversity, public health, soil, water and air.

Current mainstream livestock development is leading us into a cul-de-sac, wasting precious resources, and making matters worse, instead of focusing on fundamentals and searching for models that are in tune with Planetary Boundaries. But looking at the efforts of the leading institutions in the field – here I am looking at you, FAO and ILRI – , this is not happening.

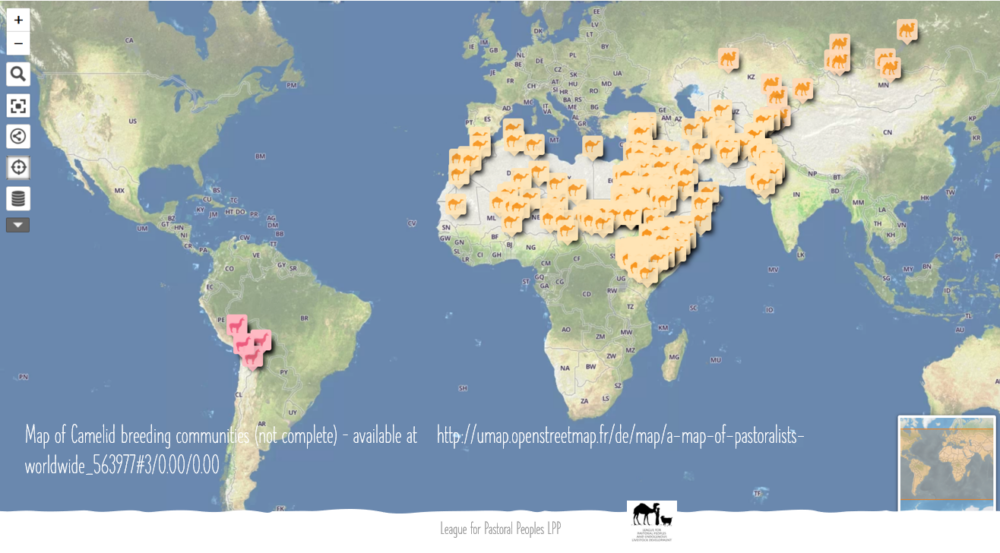

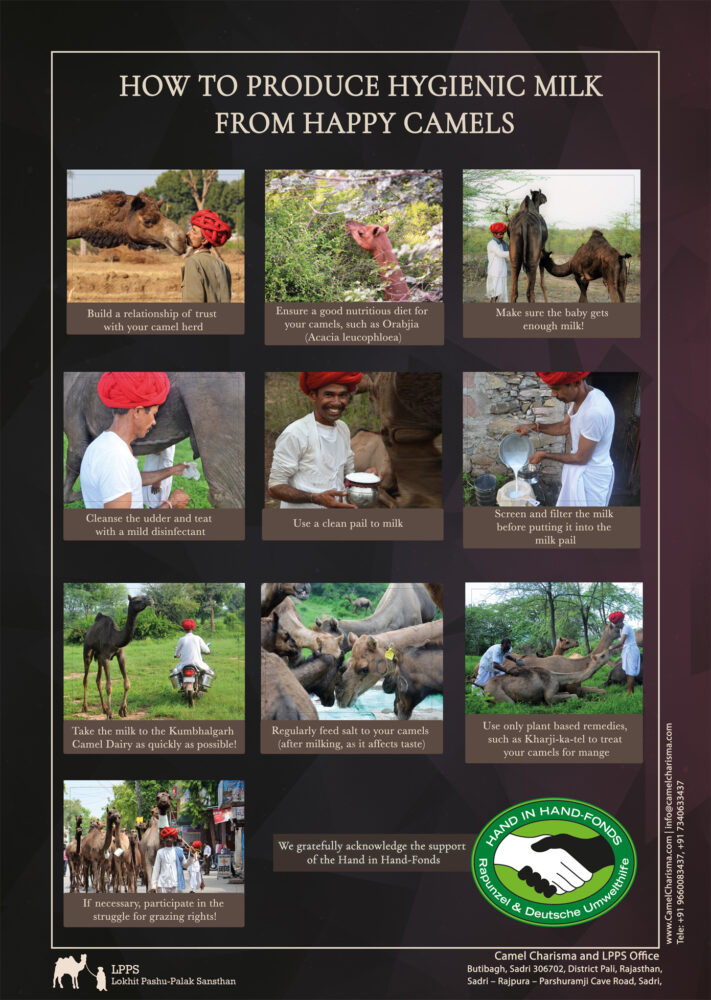

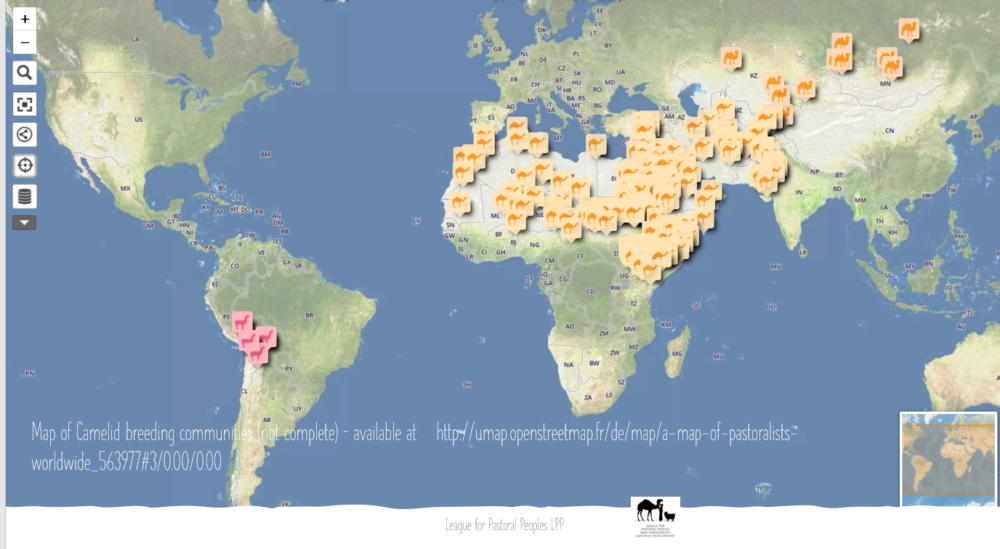

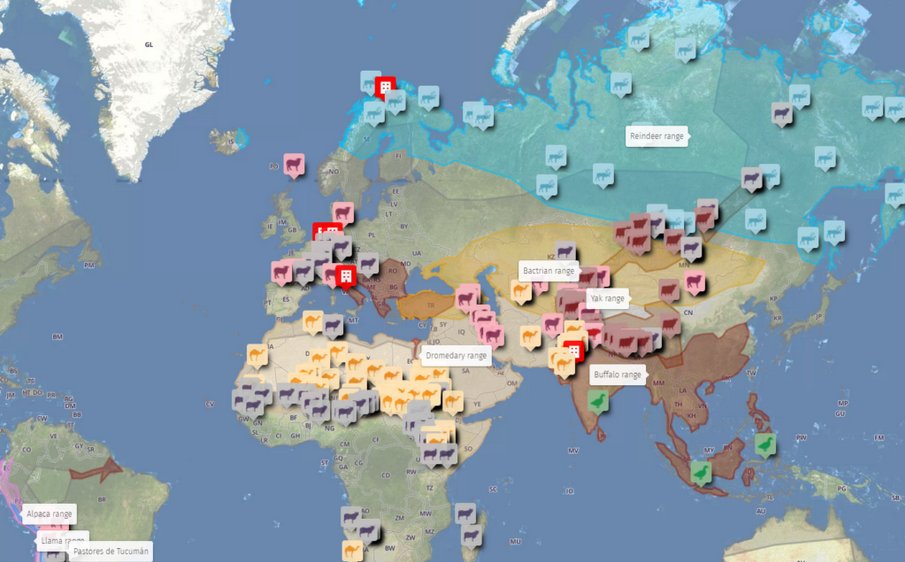

At the same time, those livestock dependent people who have, for hundreds of years – and longer – managed livestock as part of nature and without any fossil fuels, the world’s pastoralists, are under pressure practically everywhere, especially from mining and green energy projects. Why are these issues not taken up by the organizations that supposedly care about livestock and poverty alleviation? One wonders to what extent their research agenda is determined by corporate rather than public interest.

Follow

Follow