An article entitled Reducing food’s environmental impacts through producers and consumers just published in Science magazine and widely broadcasted by The Guardian and The Independent newspapers is making some startling claims. For this monumental meta-study, the authors J. Poore and T. Nemecek compiled data from 38,700 farms in 119 countries and analysed the environmental footprint of 40 major food categories with regards to Greenhouse Gas emissions, land use, freshwater withdrawals, eutrophication and acidification. Their conclusion is that even the most benignly produced meat and dairy products have a far worse environmental impact than plant foods: ..” meat, aquaculture, eggs,and dairy use ~83% of the world’s farmland and contribute 56 to 58% of food’s different emissions, despite providing only 37% of our protein and 18% of our calories” and recommend that “avoiding meat and dairy is the ‘single biggest way’ to reduce your impact on Earth”.

While the attention to the environmental impact of agriculture and food production is welcome, the conclusions are over-simplified, misleading in some aspects and very Western-centric.

This starts with the data that overwhelmingly derive from North America, Brazil, Europe, China and Australia. As the map provided in the supplementary materials illustrates hardly any studies from the African and Asian drylands have been included, reflecting the absence of Life Cycle Assessments from these countries. We can not blame this uneven data scenario on the authors, but it indicates that pastoralist systems were not included in the study.

Emphasizing that livestock provides just 18% of calories is totally misleading, since livestock is not kept to provide calories but to convert low quality feed into high quality proteins with essential amino acids that can not be sourced from plants. Its akin to saying there are 50 times more cars than trucks in the world but they only transport less than 2% of the goods.

Then there is the statement that livestock takes up 83% of farmland. The term “takes up” conjures up a situation where this land is exclusively used by livestock and not used for anything else. In reality, crops and livestock are largely integrated, as they should be. In addition, large parts of the world are non-arable – they are too dry, too step, too cold, too hot to be able to be cultivated – but they can still used for food production by means of herding livestock. Statistically these areas are classified as “permanent pastures” and are more than double the size than arable land. So its only logical that livestock can be found over a much larger part of the world than crops.

Most remarkably, the authors come to the conclusion that “without meat and dairy consumption, global farmland use could be reduced by more than 75% – an area equivalent to the US, China, European Union and Australia combined – and still feed the world.”

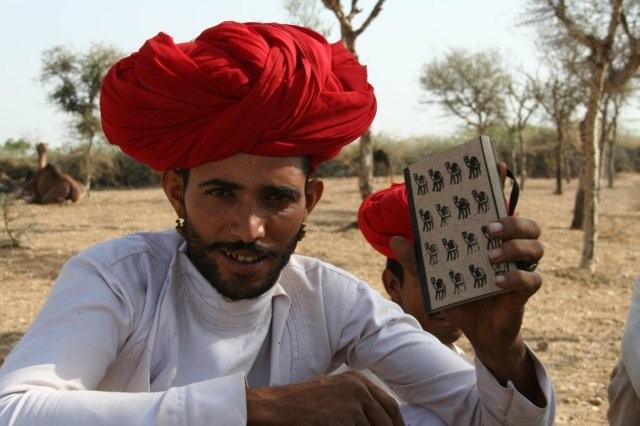

To achieve a reduction of such magnitude, we would have to stop raising livestock in the non-arable areas mentioned. Neither the authors of the study nor the journalists seem to be aware that if you remove livestock from these regions, which include the vast drylands of Africa and Asia, as well as mountainous areas in Asia and parts of Latin America, the local populations will lose their livelihoods. In these so-called marginal areas people have co-existed with and depended on livestock for millennia: reindeer herders in the tundra; yak herders in Asia’s high altitude zones; keepers of Bactrian camels and dromedaries in the deserts; nomads relying on cattle, sheep, and goats in the semi-arid steppes and savannahs.

If they are to stop livestock production, they will either starve or have to vacate the area. Thus such a blanket advisory to stop eating meat and dairy is an irresponsible recipe for disaster in already impoverished parts of the world and for people for whom livestock represents a much better survival option during the frequent droughts than growing of crops.

Yes, the world as a whole needs to drastically reduce its consumption of livestock products, and every vegan or vegetarian in the Global North, Brazil and China is welcome. But nobody can extend that recommendation to the people whose livelihoods depend on livestock in the semi-arid and arid parts of the world! For this reason, I would really recommend that the authors of the study and the journalists formally retract that particular statement and reword their conclusions to include this particular caveat.

Even in Europe and North America we need to retain some livestock in the system, as it is crucial for the provision of organic manure and – through grazing – for the conservation of biodiversity. Grazing is the most common nature conservation measure in Germany and its shepherds obtain the major income from such ‘environmental services’ rather than from the sale of products. As a new friend on Twitter, Ariel Greenwood who grazes cattle for conservation in California expressed it: We should limit consumption of animal products to those raised in an ecologically restorative way.

There is one statement by Joseph Poore that I totally agree with: The large variability in environmental impact from different farms does present an opportunity for reducing the harm, without needing the global population to become vegan. If the most harmful half (my emphasis) of meat and dairy production was replaced by plant-based food, this still delivers about two-thirds of the benefits of getting rid of all meat and dairy production.

Can we agree which is the most harmful half of meat and dairy production?

Follow

Follow