‘There is a disconnect between what we feed animals and food science’

(Dr. Sylvain Charlebois @foodprofessor)

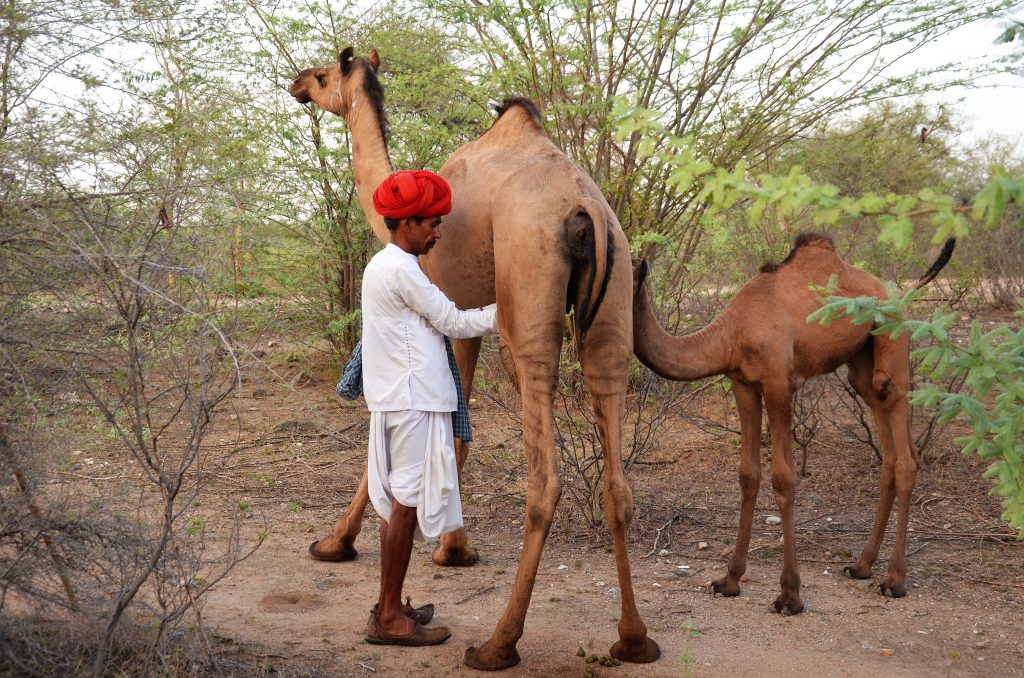

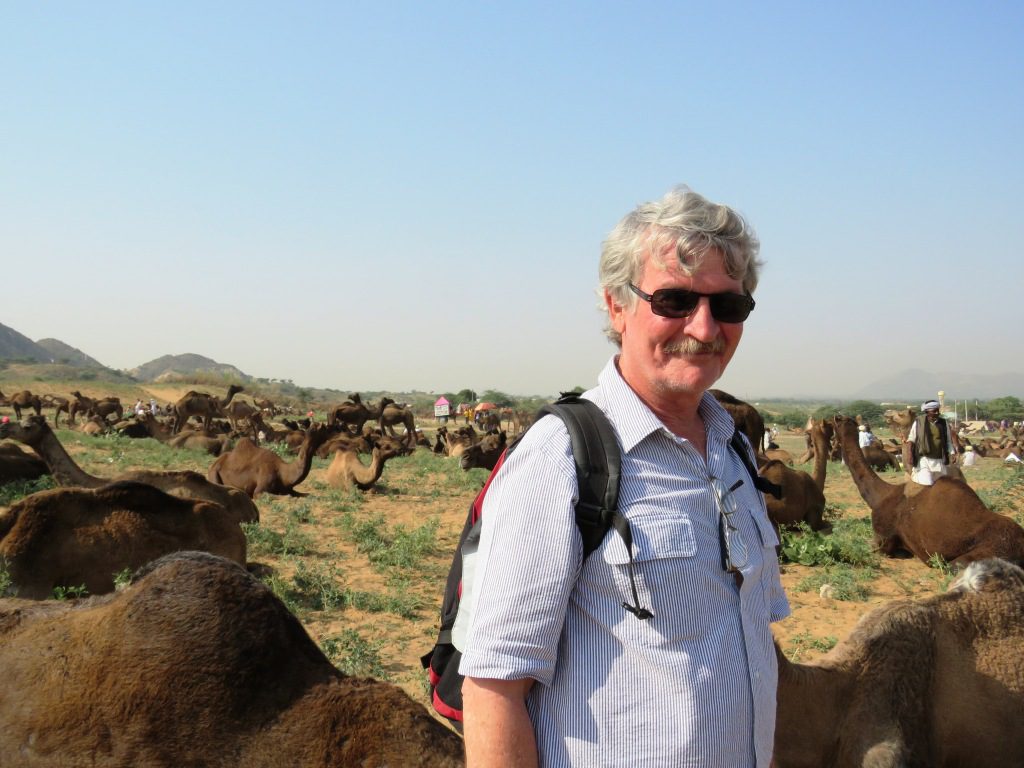

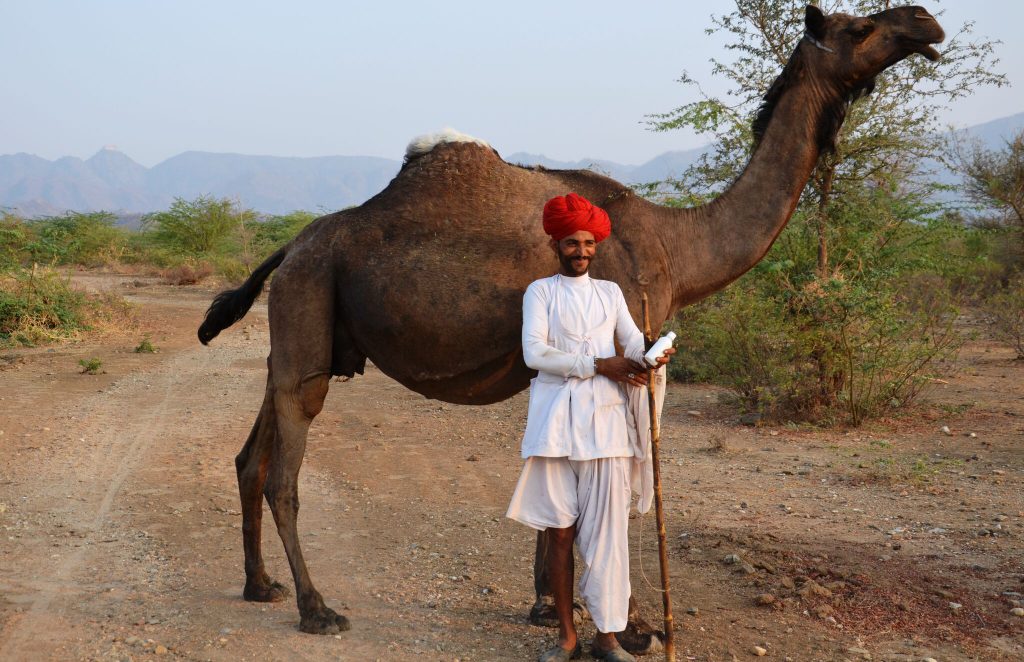

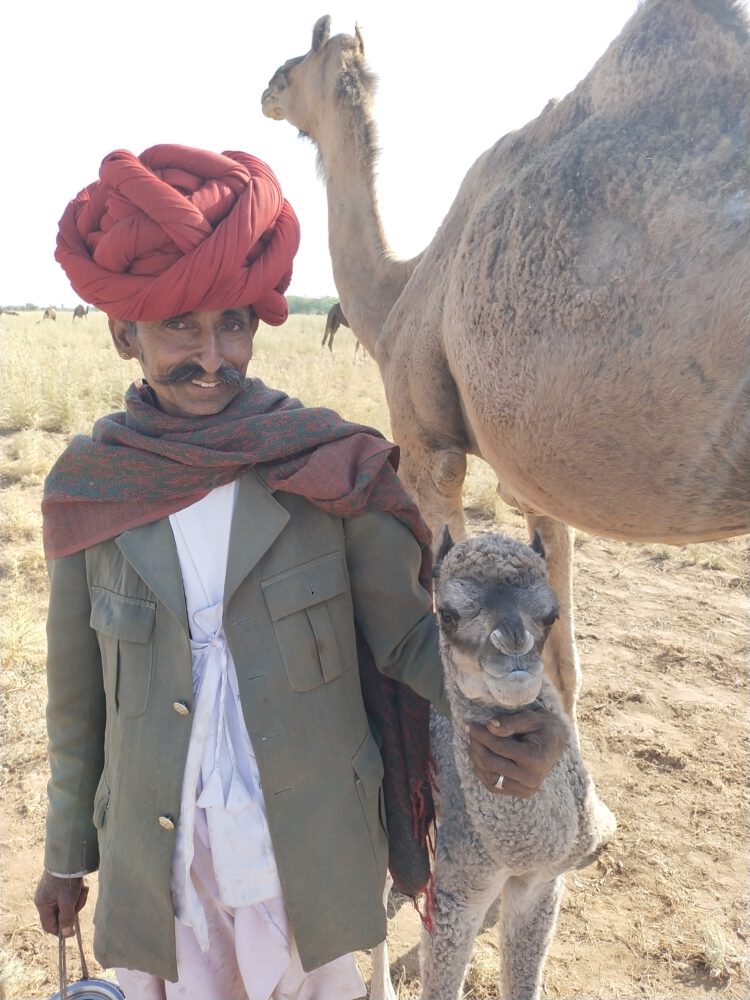

The camels that I work with and that supply the milk for the Kumbhalgarh Camel Dairy are said by their Raika keepers to feed on 36 different ayurvedic plants. It varies seasonally which plants they nosh on: forest trees and vines during the monsoon, and pods of acacia trees in the summer. At this time of year, in February, they are roaming around on fields that are totally covered in the Indian Globe Thistle – Echinops echinatus – a tall and spiky plant that no other livestock will touch. Locally known as unt kantalo (‘camel thistle’), it makes the milk incredibly sweet, as well as foamy. It tastes like ambrosia. Of course our camel breeders are addicted to the elixir, but even our esteemed visitor, Dr. Tatti from Prompt Innovations could not get enough of it during a recent visit!

After returning from the (thistle) field, I looked up Echinops echinatus and found out that all kinds of medicinal properties are ascribed to it: antifungal, analgesic, diuretic, reproductive, hepatoprotective, antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, wound-healing, antipyretic, and antibacterial properties. Its even good for your sex-life! (Is that why camel milk is regarded as an aphrodisiac?)

By indulging in thistles, camels actually provide three different kinds of services:

- They de-weed which is appreciated by the farmers who own the land and who hate unt-kantalo, that creeps up during the time their land lies fallow.

- They provide organic manure and deposit it precisely where it is needed

- They produce this wonderful milk that I can only liken to ambrosia in taste.

- They also produce offspring!

Its almost miraculous how the camels transform an unwanted material into a health tonic and at the same time replenish and fertilize the soil. Pure pastoral alchemy! And it exemplifies how livestock is best used, in sync with nature: pastoralism only gives, it does not take.

Canada’s ‘Buttergate’: palm oil in dairy feed

I can’t help but link this scenario to a scandal that is currently engulfing the Canadian dairy industry: the fact that butter no longer softens at room temperature, apparently due to cows being fed with supplementary palm oil. Palm oil, of all things! When it is known that a. its cultivation is one of the most biodiversity destroying activities and b. it has also been associated with negative effects on human health. The Canadian public is outraged, as many have been buying butter to avoid palm oil, and dairy farmers are well subsidized in order to produce healthy food, according to Dr. Sylvain Charlebois, senior director at Dalhousie University’s Agri-Food Analytics Lab. In an interview he also points at a disconnect between what animals are fed and how this affects human/public health. I think this is a crucial point that needs to be remedied urgently, because it is of such relevance to the much touted One Health approach, which considers human, animal and ecological health as interconnected. It would certainly help validate pastoralist food production!

Is pastoralism naturally ‘net zero’?

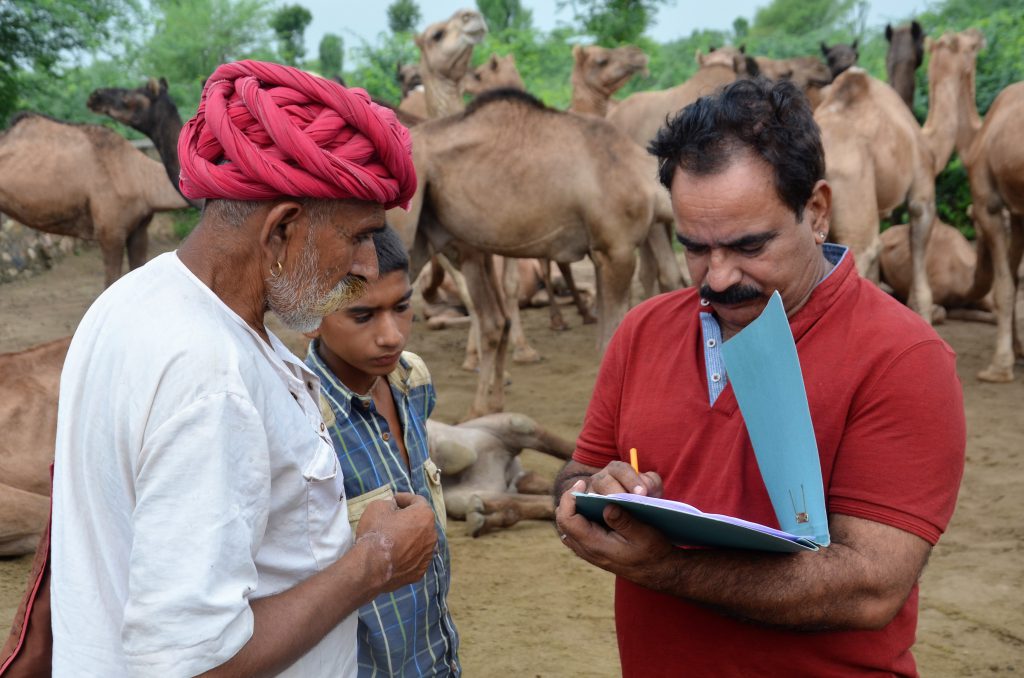

And there is another hot issue to which I would like to link the observations on the thistle field: The dairy sector is now feeling the heat from the anti-livestock propaganda and is making an earnest attempt to become ‘net zero‘ in terms of Green House Gas emissions by 2050. One of the approaches they are promoting is to process manure into fertilizer. I am wondering if pastoralists are not already there at ‘net zero’ dairy production, because their systems are entirely solar powered and they use practically no fossil fuels. At the same time, they reduce the need for chemical fertilizer (whose production is extremely GHG intensive) and also the need for weed killers. It would be great if a credible research organization could do a life cycle analysis of this particular camel dairy system, as well as other pastoralist production systems!

If you are interested to learn more about the unique camel dairy system described and would like to support it, please go to our Patreon page here.

Follow

Follow