I am currently reading a fabulous (in the true sense of the word) book by Kelly Carew ‘Beastly. A new history of animals and us‘. In it she describes her revulsion as a child to the Biblical story of Cain and Abel, the sons of Adam and Eve. The former was a farmer, the latter a shepherd and inexplicably God preferred the offering of Abel (a lamb) to those of Cain (harvested crops).

I am not a Biblical scholar, but from what I understand the name Abel is derived from ibl, the Arabic word for camel, and the name Cain was associated with metal forging and copper mining. According to one source :

The Biblical conflict between Cain and his brother Abel is an iconic story of the conflict created by the copper mining operations in the Negev. Copper was mined and smelted on site using local brushwood as fuel. The mining operations denuded the area where the Bedouin and caravan tribes grazed their goats and camels causing a conflict between the miners and the shepherding Bedouin and camel herders. The conflict is represented in the Cain and Abel saga in which Cain represented the mining interests and Abel represented Bedouin pastoralism as well as the caravan tribes in the frankincense trade.

If this interpretation is correct, then it is no wonder that God preferred the sheep- or camel herding Abel to the miner/farmer Cain. Because herding livestock is the one systematic way of food production that respects and does not structurally modify ‘God’s creation’ , i.e. the Earth’s natural biodiversity and replace it with monocultures (or sometimes polycultures). It is by far the most natural way of producing food, one whose only prerequisite is trust and good communication between humans and herd animals. It requires no fossil fuels, no pesticides or any other -cides, no fertilizer. It is a much more efficient way of protein production than factory farming and feedlotting – systems which consume more human edible protein than they generate although they are conjured up as necessary to feed the world.

As Keggie Carew eloquently and emotionally conveys in Beastly, we KNOW that industrial livestock faming serves as a n incubator for zoonotic diseases that can jump over to humans, and we also KNOW that replacing tropical rain forests with palm oil plantations and other mono-cultures exposes humans to new disease vectors. We are also realizing that the most effective way of stablizing the climate is by conserving biodiversity, and that these two environmental issues can not be disentangled.

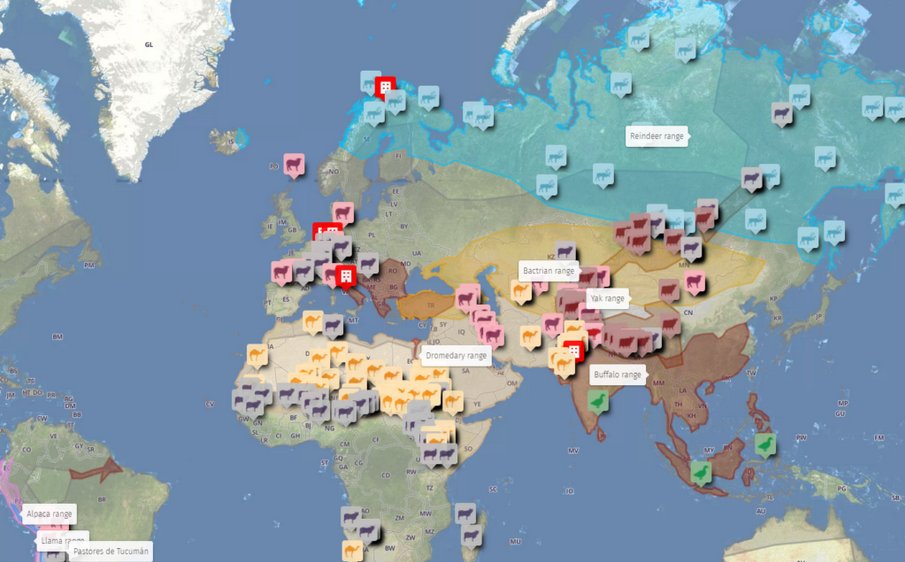

We know all this, yet as an international community we are paralysed. We continue to pump carbon dioxide into the air, pour asphalt over the ground, and support and subsidize industrial and factory farming. Not that we are not concerned about ‘conservation’: At the last Conference of the Parties to the United Convention on Biodiversity held in Montreal in December 2022, the world agreed on conserving 30% of the earth’s land and sea through the establishment of protected areas (PAs) and other area-based conservation measures (OECMs).

Yet, this was a highly controversial target opposed by many indigenous peoples because ironically and tragically they are the ones who are prone to be affected negatively. It is in their ancestral territories that these conservation areas are likely to be established, because they most closely resemble nature.

The 30% target would be fine, if we now supported pastoralists and other indigenous peoples, to continue stewarding biodiversity. But Conservation with a big C has a bismal record with respect to the rights of indigenous peoples and it seems as if only affluent western wildlife agencies come out on top. Although ‘fortress conservation’ has become discredited, in practice it still predominates.

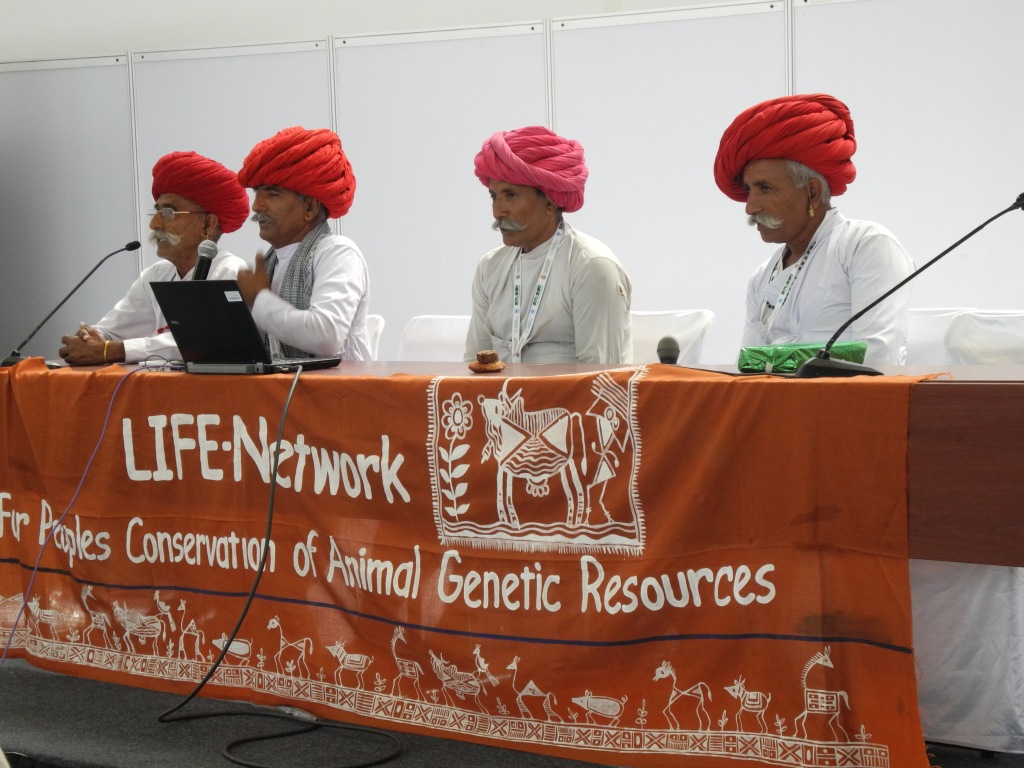

Look at the Raika camel and sheep/goat herders of Rajasthan – people who produce milk and meat in a humane and ethical way, while also stewarding the environment. They tolerate that leopards prey on their animals without taking retribution, ther herds support germination and regeneration of local acacia trees, while also providing organic manure. Yet these services go unrecognized and these genuine conservers of biodiversity are regarded as threat to conservation and have lost their long-standing grazing rights in places such as the Kumbhalgarh Wildlife Sanctuary.

No wonder few young people want to continue in this profession which combines food production wth environmental services.

Reinstating the rights of pastoralists to their ancestral territories and prioritizing them over mining and other interests would go a long way towards saving both biodiversity and limiting climate change. It would be a measure that does not cost anything and have many positive social percussions as well. But, alas, at the moment I do not know of any single country where this is happening (although I would love to be told that I am wrong). Amazingly, the story of Cain and Abel is still very relevant more than two thousand years later.

Follow

Follow