On 22 May, the International Day of Biological Diversity, we must recall that food production is the world’s worst enemy of biodiversity. When we cultivate crops, we replace native plant assemblages with monocultures and, in order to protect them, usually apply rounds of pesticides, herbicides, fungicides and chemical fertilizer. This cocktail eliminates the micro-organisms and insects at the bottom of the food chain, depleting amphibia, reptiles, birds, and mammals, eventually leading to sterile landscapes.

Pastoralism is the only exception from this predominant model of fulfilling our nutritional needs: the natural plant cover is not removed and herd animals directly convert biodiversity into edibles, circumventing all the toxic and carbon-intensive steps involved in most crop production. It is based on natural biological processes and is powered by the sun. Because of the absence of un-natural inputs, pastoral areas are the original ‘lands of milk and honey’.

Areas where pastoralists roam are often picked for setting up wildlife sanctuaries or national parks. This is no accident. In the absence of crop cultivation, biodiversity thrives. “If you have pastoralists, you do not need a national park” emphasizes Jesus Garzon-Heydt, one of Spain’s most prominent conservationists. He is one of the movers and shakers behind the revival of Spain’s transhumance and its ancient drove roads, the Cañadas. In medieval Spain, a network of drove roads was established by royal decree that facilitated the semi-annual movement of five million sheep, goats, pigs, cattle and horses between their winter quarters in the southern and coastal lowlands to summer pastures in the mountainous areas of the north. The Cañadas were up to 75 meters wide, with a total length of around 125,000 km and covering a surface of more than 420,000 hectares of common property, equivalent to 1% of Spain’s total area. This pastureland buzzes with biodiversity in terms of plants, butterflies, and beetles. Vultures made a comeback when transhumance was revived[i].

Research on Spain’s transhumant sheep also led to another important ecological discovery: The role of migratory livestock as “seed taxis”. Sheep transport thousands of seeds over hundreds of kilometres in their fleece[ii]. With changing climates, this can be an important vehicle for plants to move into new areas that fit their requirements and thereby prevent their extinction. Besides seeds, sheep can also carry lizards, beetles and grasshoppers, aiding their movement to new biotopes and adaptation to a changing biome during climate change. In Germany sheep were found to redistribute up to 8500 seeds from 57 species[iii]. The monetary value of the seed transportation services of a flock of sheep amounted to some 4500 EURO for a 200 head flock.

Sheep don’t just do this by default and the nature of their wooliness, some herders make conscious efforts to disperse the seeds of preferred plants. Pastoralists in the Islamic Republic of Iran pack seeds in little bags and hang these around the necks of their sheep. During grazing the seeds drop out through little holes in the bags and are worked into to the ground by the sheep’s hooves[iv].

It is not just that livestock transport seeds, they also aid their germination through scarification. ‘Scarification’ has nothing to do with tattoos, but is a botanical term that refers to weakening the coat of a seed, so that it can break up and germinate. Many acacia trees, for instance, have very hard seed coats and their seeds need to pass through the stomach of a ruminant in order to be able to sprout. After they have scarified the seeds, livestock also conveniently trample them into the ground like a forest gardener.

‘Trampling’ has other ecological effects as well, mostly positive, although it all depends on the intensity and the context. The depressions left by hooves fill with water and become mini-habitats for insects and amphibians, which then provide food for all kinds of birds and mammals. And here we come to the general role of grazing animals at the bottom of the food chain. Their droppings are powerful incubators for a huge diversity of beetles and buzzing insects that not only feed populations of insectivorous birds, bats and reptiles, but also break down the manure into its constituents that feed soil bacteria and loosen up the soil. The presence or absence of grazing animals in a landscape makes a huge difference to its biodiversity.

Researchers in Germany have concluded that mechanical mowing of meadows has a disastrous effect on insects, killing up to 80% of cicadas, for instance. They see it as a one of the major factors in the dramatic loss of insect, bird, amphibian and reptile populations.that the country has experienced.[v] This is one of the reasons why ‘grazing’ is the country’s most popular nature conservation strategy and shepherds make more of their income from conservation activities than the sale of products.

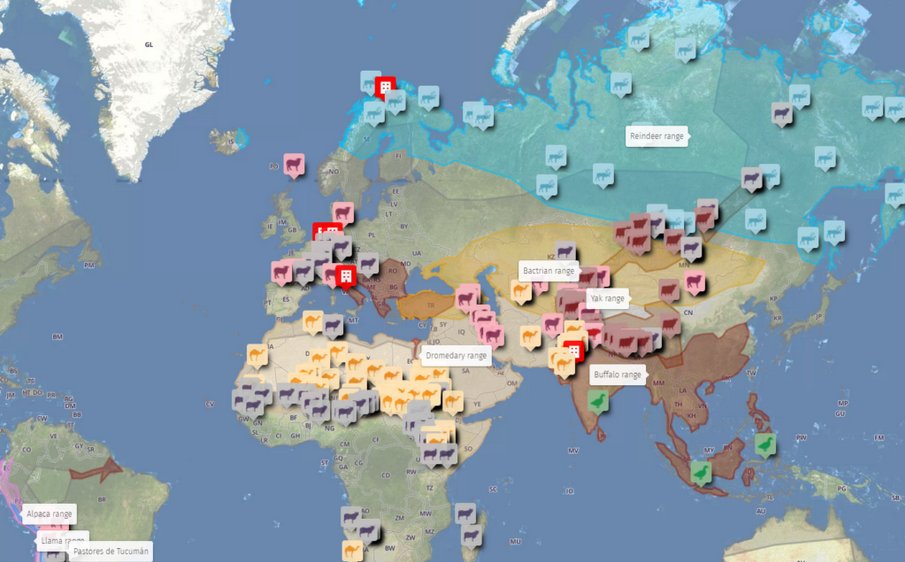

Why mapping pastoralism?

Yet, livestock has turned into a bogeyman and is blamed for .many of our planetary problems. Meat is projected as the world’s biggest environmental ill. There is truth in these accusations, but they do not pertain to pastoralism which works on different principles than intensive ways of livestock production. So it is crucial that we make the distinction clear and draw attention to the potential of pastoralism for the ‘nature positive production‘ that is so prominently envisioned in the context of the International Food System Summit. By mapping pastoralism we can visualize the extent of already existing ‘nature positive production’ and that we need to support these systems and communities if we want to put our planet on a more sustainable trajectory. On 25th May, at 2 p.m. CEST, there will be an introduction to this crowd-sourced mapping project for which you can still register here.

[i] Pedro P. Oleaa,*, Patricia Mateo-Tomás . 2009. The role of traditional farming practices in ecosystem conservation: The case of transhumance and vultures. Biological Conservation 142 (2009) 1844–1853

[ii] P. Manzano and J. Malo, 2006. Extreme long‐distance seed dispersal via sheep. Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment 4(5):244-248.

[iii] Fischer, S., Poschlod, P., & Beinlich, B. (1996). Experimental Studies on the Dispersal of Plants and Animals on Sheep in Calcareous Grasslands. Journal of Applied Ecology, 33(5), 1206-1222. doi:10.2307/2404699

[iv] Koocheki, A. 1992. Herders care for their land. ILEIA Newsletter, 8(3): 3

[v] Nickel H 2017. Evolution im Naturschutz: Von der Weide zur Wiese und zurück? https://www.bfn.de/fileadmin/BfN/ina/Dokumente/Tagungsdoku/2017/02_Nickel_Wiese_oder_Weide.pdf

Follow

Follow